The Mysterious Chacmool

By Victor Zugg

Reprinted Courtesy of Popular Archaeology Magazine. Originally published in the Fall 2015 edition.

The Maya of Chichen Itza and the Toltec of Tula were the center of different civilizations, occupied mostly different eras, different regions, and spoke different languages. But there are similarities between these two cities that indicate a strong connection that is not well understood and furiously debated, even to this day. This is an exploration of that connection, with a focus on what is probably its most intriguing aspect: the mysterious chacmool.

The chacmool is distinctive statuary that has been found predominately at just the two Mesoamerican sites: Tula, home of the Toltec civilization, near present-day Mexico City, and Chichen Itza, nearly twelve hundred kilometers to the east, in the northern Yucatan Peninsula deep in Maya territory. In fact, the chacmool presence at Chichen Itza is one of the elements that has led many noted scientists and scholars to conclude that the Nahuatl speaking Toltecs of the much smaller Tula invaded the Maya and occupied their site at Chichen Itza, possibly around AD 1000. For those who side with this Toltec invasion theory, their thinking is that the chacmool was an exclusive Toltec expression that originated in Tula. But did it?

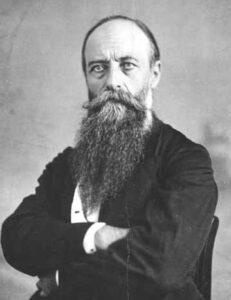

Three-dimensional, free-standing, and life-sized, the chacmool is a male figure carved from a single stone. He’s reclined on his back with feet and elbows down, stomach horizontal, knees, chest, and head up, head turned 90 degrees. From chacmool to chacmool details vary but the form remains fairly constant. The actual name given by the Maya/Toltec for this statuary is unknown. It was Augustus Le Plongeon (1825 – 1908), a British/American photographer and antiquarian, who coined the “chaac mool” name in 1875 when he excavated one of the figures from what has come to be known as the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars, in Chichen Itza. He believed the statue represented a warrior prince with that name who once ruled Chichen Itza. The spelling was changed to “chacmool” in the published account of Le Plongeon’s find.

August Le Plongeon never gave the exact location of where he found his chacmool. Most sources claim he found it buried in the rubble of what has come to be called the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars. But at least one source, the National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City) catalog, identifies it as having been found in the Venus Platform. Both platforms are located roughly between the El Castillo pyramid and the great Ball Court of Chichen Itza. So, precisely where did he find the chacmool? In early 1876, Le Plongeon, in a letter to the president of Mexico asking for permission to transport the chacmool to the American centennial in Philadelphia, described the site, but not the location, where he found the chacmool.

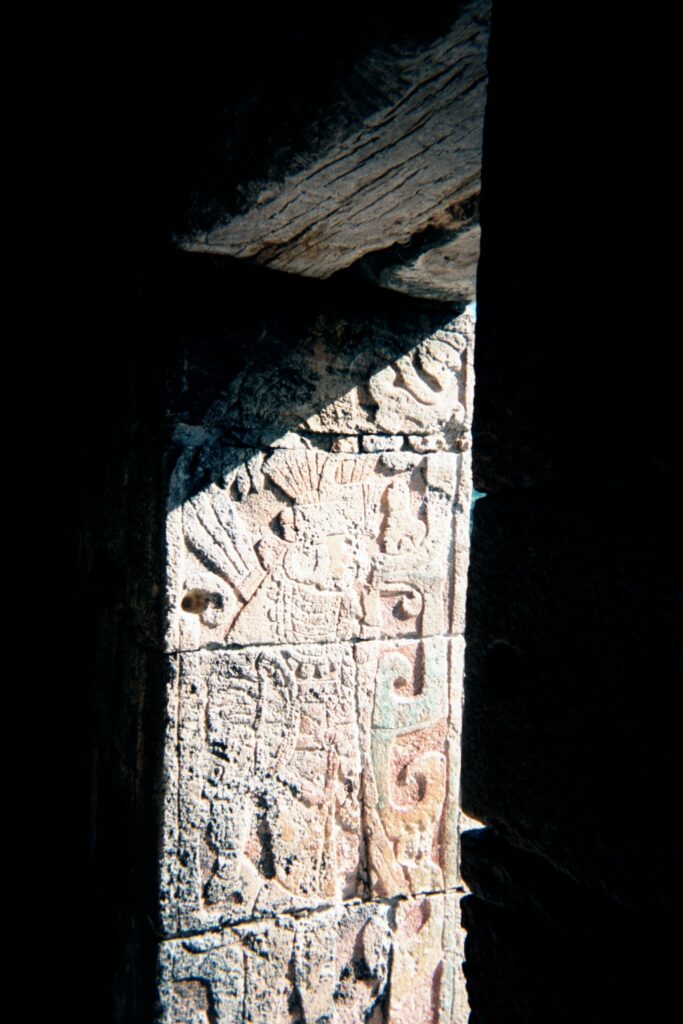

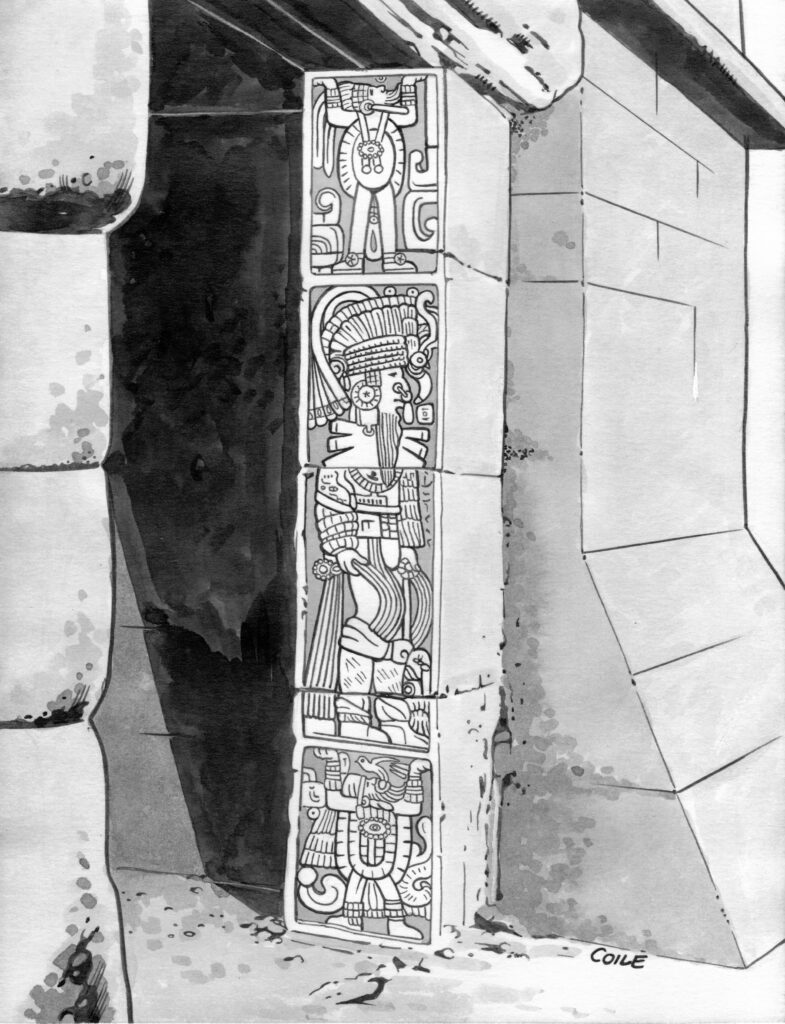

August Le Plongeon never gave the exact location of where he found his chacmool. Most sources claim he found it buried in the rubble of what has come to be called the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars. But at least one source, the National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City) catalog, identifies it as having been found in the Venus Platform. Both platforms are located roughly between the El Castillo pyramid and the great Ball Court of Chichen Itza. So, precisely where did he find the chacmool? In early 1876, Le Plongeon, in a letter to the president of Mexico asking for permission to transport the chacmool to the American centennial in Philadelphia, described the site, but not the location, where he found the chacmool. “Guided, as I have just said, by my interpretations of the mural paintings, bas-reliefs, and other signs that I found in the monument raised to the memory of the Chief Chaacmol, by his wife, the Queen of Chichen, by which the stones speak to those who can understand them, I directed my steps, inspired perhaps also by the instinct of the archaeologist, to a dense part of the thicket. Only one Indian, Desiderio Kansal, from the neighborhood of Sisal-Valladolid, accompanied me. With his machete he opened a path among the weeds, vines and bushes, and I reached the place I sought. It was a shapeless heap of rough stones. Around it were sculptured pieces and bas-reliefs delicately executed…I have found amidst the forest, eight meters under the soil, a statue of Chaacmol, of calcareous stone, one meter, fifty-five centimeters long, one meter, fifteen centimeters in height, and eighty centimeters wide….” Chichen Itza was a much different place in 1875. Monuments, that have since been restored to their earlier glory, were just piles of rubble then. But it seems fairly clear that the murals and hieroglyphics Le Plongeon said he deciphered, and which directed him to the location of the chacmool mound, were in the Temple of the Jaguars which was then, and is today, connected to the ball court. Murals and reliefs inside this temple are, to a lesser degree, still discernible. Some distance from there he found the chacmool buried in a mound. The Temple of the Jaguars is separate and distinct from the Platform of the Jaguars and Eagles; they are about 100 feet apart. In both his letter to the Mexican president and later in his Vestiges of the Maya he said he also found in the mound bas relief plates depicting a spotted jaguar and a bird. Photos of these plates were included with the twelve that Le Plongeon took during his excavation of the chacmool. These plates are mounted on the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars today. So, it is most probable that Le Plongeon found his chacmool in the mound that has since been restored to become the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars. By the way, the Mexican president denied Le Plongeon’s request to transport the chacmool to Philadelphia. Instead, Mexican authorities sent troops to the area around Chichen Itza and were able to locate the chacmool, which Le Plongeon had hidden in a thicket about two miles from where he found the statue. Mexican authorities moved the chacmool first to Merida, the largest city in the area, where it was displayed for a few days, and then on to Mexico City, where it remains to this day. It is often reported that the Mexican navy intercepted Le Plongeon’s boat as he tried to remove the statue from the country. This is not true. Le Plongeon was exploring other areas of the Maya at the time Mexican authorities found his chacmool.

“Guided, as I have just said, by my interpretations of the mural paintings, bas-reliefs, and other signs that I found in the monument raised to the memory of the Chief Chaacmol, by his wife, the Queen of Chichen, by which the stones speak to those who can understand them, I directed my steps, inspired perhaps also by the instinct of the archaeologist, to a dense part of the thicket. Only one Indian, Desiderio Kansal, from the neighborhood of Sisal-Valladolid, accompanied me. With his machete he opened a path among the weeds, vines and bushes, and I reached the place I sought. It was a shapeless heap of rough stones. Around it were sculptured pieces and bas-reliefs delicately executed…I have found amidst the forest, eight meters under the soil, a statue of Chaacmol, of calcareous stone, one meter, fifty-five centimeters long, one meter, fifteen centimeters in height, and eighty centimeters wide….” Chichen Itza was a much different place in 1875. Monuments, that have since been restored to their earlier glory, were just piles of rubble then. But it seems fairly clear that the murals and hieroglyphics Le Plongeon said he deciphered, and which directed him to the location of the chacmool mound, were in the Temple of the Jaguars which was then, and is today, connected to the ball court. Murals and reliefs inside this temple are, to a lesser degree, still discernible. Some distance from there he found the chacmool buried in a mound. The Temple of the Jaguars is separate and distinct from the Platform of the Jaguars and Eagles; they are about 100 feet apart. In both his letter to the Mexican president and later in his Vestiges of the Maya he said he also found in the mound bas relief plates depicting a spotted jaguar and a bird. Photos of these plates were included with the twelve that Le Plongeon took during his excavation of the chacmool. These plates are mounted on the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars today. So, it is most probable that Le Plongeon found his chacmool in the mound that has since been restored to become the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars. By the way, the Mexican president denied Le Plongeon’s request to transport the chacmool to Philadelphia. Instead, Mexican authorities sent troops to the area around Chichen Itza and were able to locate the chacmool, which Le Plongeon had hidden in a thicket about two miles from where he found the statue. Mexican authorities moved the chacmool first to Merida, the largest city in the area, where it was displayed for a few days, and then on to Mexico City, where it remains to this day. It is often reported that the Mexican navy intercepted Le Plongeon’s boat as he tried to remove the statue from the country. This is not true. Le Plongeon was exploring other areas of the Maya at the time Mexican authorities found his chacmool.

In total, archaeologists have so far found 14 chacmools at Chichen Itza, 12 at Tula, and a few others scattered at various other sites: Tenochtitlan (Templo Mayor), Michoacan, Queretaro, Acolman, and Tlaxcala, all near Tula, along with Cempoala in the state of Veracruz on the Gulf coast, Quirigua in Guatemala, Tazumal in El Salvador, and Las Mercedes in Costa Rica. Given the context of the finds, none predate the ones found at Chichen Itza, the earliest examples of which date to AD 800 – 900. The Tula chacmools date to AD 900 – 1200. Also, chacmools found at Chichen Itza represent a variety of sizes and styles, while the Tula chacmools are more standardized. Scholars theorize that variety might indicate experimentation, which might indicate origin, in this case Chichen Itza. The dating would seem to support that theory.

The actual function of the chacmool is unknown but, given their placement and iconography, they were probably more than just an artistic expression. Likely the figure had more to do with religious or sacrificial ceremony. At least three chacmools found in the area of Tula include markings linked to Tlaloc, the Aztec/Toltec rain god. The figure excavated by Le Plongeon in Chichen Itza includes what appears to be Tlaloc imagery on the ears. And a figure found in Chichen Itza’s El Castillo pyramid includes what appear to be tiny Chac symbols. Chac was the Maya rain god. But why the concentration at just the two sites; what is the connection between Chichen Itza and Tula?

Most scholars agree there are two distinct architectural styles in Chichen Itza, divided between the south and north sections. The oldest monuments and buildings are in the south section and were constructed in the Puuc architectural style, the same style used in the construction of several other cities and sites in the Puuc region (Uxmal, Kabah, Sayil, and Labna). Chichen Itza is located on the eastern edge of this region. Many of Chichen Itza’s Puuc structures are inscribed with relief hieroglyphics to include Maya long count dates. The earliest of these dates equate to AD 878 – 906 in the present-day calendar.

However, some of Chichen Itza’s buildings and monuments in the north section are newer, built over earlier intact structures, and reflect a style some say is reminiscent of that in Tula. These north section structures have few inscriptions and no long count dates, so the newer construction is difficult to date. Noted French archaeologist, Claude-Joseph Désiré Charnay (1828 – 1915), is credited with first noticing the Tula similarities at Chichen Itza in 1887. According to scientists and scholars, Toltec architectural elements at Chichen Itza include columns (in place of some walls), a sloping batter at the base of exterior walls and platforms, low masonry banquettes or benches built into the walls, colonnades, carved stone atlantean columns or supports, and serpents, carved and painted.

There are two particularly interesting Chichen Itza north structures: the Temple of the Warriors and the nearby El Castillo, the large stepped pyramid in the central plaza. Both were built over existing structures. Tula includes counterpart versions of these same monuments. Pyramids in both cities are referred to by the name of their respective serpent entities: the Temple of Kukulcan at Chichen Itza, and the Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Tula. Most scholars believe Kukulcan and Quetzalcoatl are one in the same; both names mean “feathered serpent”.

Chichen Itza’s El Castillo, also referred to as the Temple of Kukulcan, is a stepped pyramid on a 55.3 meter square base composed of limestone blocks arranged in 9 platforms. The top platform houses the 13.42 x 16.5 meter temple building. The entire structure, including the 6 meter high temple at the top, stands 30 meters. A 91-step staircase running bottom to top bisects each of the four sides. Including the one step for the top platform, there are 365 total steps, the number of days in a solar year. The vertical sides of the 9 platforms, bisected by their respective staircase on each pyramid side, form 52 vertical panels (18 on each pyramid side). A Maya calendar cycle is 52 years. The pyramid is oriented approximately 17 degrees off of true north.

Chichen Itza’s El Castillo, also referred to as the Temple of Kukulcan, is a stepped pyramid on a 55.3 meter square base composed of limestone blocks arranged in 9 platforms. The top platform houses the 13.42 x 16.5 meter temple building. The entire structure, including the 6 meter high temple at the top, stands 30 meters. A 91-step staircase running bottom to top bisects each of the four sides. Including the one step for the top platform, there are 365 total steps, the number of days in a solar year. The vertical sides of the 9 platforms, bisected by their respective staircase on each pyramid side, form 52 vertical panels (18 on each pyramid side). A Maya calendar cycle is 52 years. The pyramid is oriented approximately 17 degrees off of true north.  Two times each year, at the spring and fall equinoxes (March 21 and September 22), this orientation allows the platform corners to throw a shadow against the side of the north staircase baluster correlating with the carved serpent head at the bottom, giving the impression of an undulating snake down the entire length of the staircase. The temple at the top includes various relief carvings, including one of a bearded man on the side of the north-east opening. This is thought by many scholars to be a depiction of Kukulcan—meaning plumed or feathered serpent—probably a chief or high priest closely associated, or perhaps confused, with an actual Maya deity. The bearded man/god is represented in all of the major pre-Columbian cultures: Kukulcan for the Maya, Quetzalcoatl for the Aztec, and Viracocha among the Inca. Reliefs and carvings of the bearded man often include what could be described as Caucasian features, another Mesoamerican mystery. While no one today knows where or how the bearded man originated, he is additionally well represented among artifacts from the Tabasco/Veracruz area of Mexico, leading many to believe the man and/or deity might have originated from at least the time of the Olmec. The Olmec culture is thought to be the mother culture of Mesoamerica. Today, El Castillo is perhaps the most well-known of the ancient Maya monuments.

Two times each year, at the spring and fall equinoxes (March 21 and September 22), this orientation allows the platform corners to throw a shadow against the side of the north staircase baluster correlating with the carved serpent head at the bottom, giving the impression of an undulating snake down the entire length of the staircase. The temple at the top includes various relief carvings, including one of a bearded man on the side of the north-east opening. This is thought by many scholars to be a depiction of Kukulcan—meaning plumed or feathered serpent—probably a chief or high priest closely associated, or perhaps confused, with an actual Maya deity. The bearded man/god is represented in all of the major pre-Columbian cultures: Kukulcan for the Maya, Quetzalcoatl for the Aztec, and Viracocha among the Inca. Reliefs and carvings of the bearded man often include what could be described as Caucasian features, another Mesoamerican mystery. While no one today knows where or how the bearded man originated, he is additionally well represented among artifacts from the Tabasco/Veracruz area of Mexico, leading many to believe the man and/or deity might have originated from at least the time of the Olmec. The Olmec culture is thought to be the mother culture of Mesoamerica. Today, El Castillo is perhaps the most well-known of the ancient Maya monuments.

In the mid-1930s a Mexican government-sponsored excavation of El Castillo (Temple of Kukulcan) disclosed the intact substructure, a pyramid within a pyramid. Workmen dug into the side of the north exterior stairs and found an internal stairway filled with dirt and debris, presumably to reinforce the structure to support the later construction of the exterior pyramid. Once the debris was removed they were able to ascend these interior stairs to the pinnacle of the inner pyramid, where they found two rooms. The inner room contained a single item: a perfectly preserved jaguar sculpture in the form of a throne or seat. The outer room also contained a single item: a perfectly preserved chacmool figure. But if the chacmool originated in Tula, as some scientists believe, how did one come to be in a Chichen Itza structure that supposedly predates Tula’s construction?

There is general consensus that the earlier El Castillo substructure was constructed prior to AD 900, which would line up with construction of the Puuc-style south section and the accepted timeline for Chichen Itza’s initial rise to dominance in the ninth century. This would have been before what is believed to be Tula’s prominence, and the construction of the major monuments there (Tula Grand) in the AD 900 – 1150 period. Also, while there may be “Toltec” architectural similarities with many of the newer structures at Chichen Itza, there is at least one notable exception. The exterior rooms on top of the El Castillo (outer) pyramid are corbelled, a technique associated with the Maya. If the Toltec were responsible for the later construction at Chichen Itza, why would there be Maya elements among the architecture? Perhaps the architecture at nearby sites will provide clues to this mystery?

The Late Classic period (AD 600 – 800) city of Uxmal is the closest major Maya city to Chichen Itza and, based on hieroglyphic dates, it appears that occupation of the two sites at least overlapped. However, at Uxmal there appear to be no real architectural similarities with Tula. Architecture at Uxmal is pure Puuc. On the other hand, the Post Classic period (AD 900 – 1500) city of Mayapan, about 100 kilometers west of Chichen Itza, is in a number of ways a smaller version of Chichen Itza. Mayapan has nearly exact replicas of monuments at Chichen Itza, including the central pyramid. Mayapan’s pyramid is smaller but it, too, has nine terraces, was built over an existing intact inner pyramid, and one of the four stairways leading to the top includes serpent balustrades. Several rectangular buildings scattered around the central plaza have columns instead of walls. So there is what could be considered Toltec similarities at Mayapan. As for the chacmool, the figure has not been found at Uxmal, which came before Chichen Itza, nor Mayapan, which came after Chichen Itza. The chacmool being absent from Mayapan is especially curious since Mayapan was supposedly, according to myth, built by people from Chichen Itza.

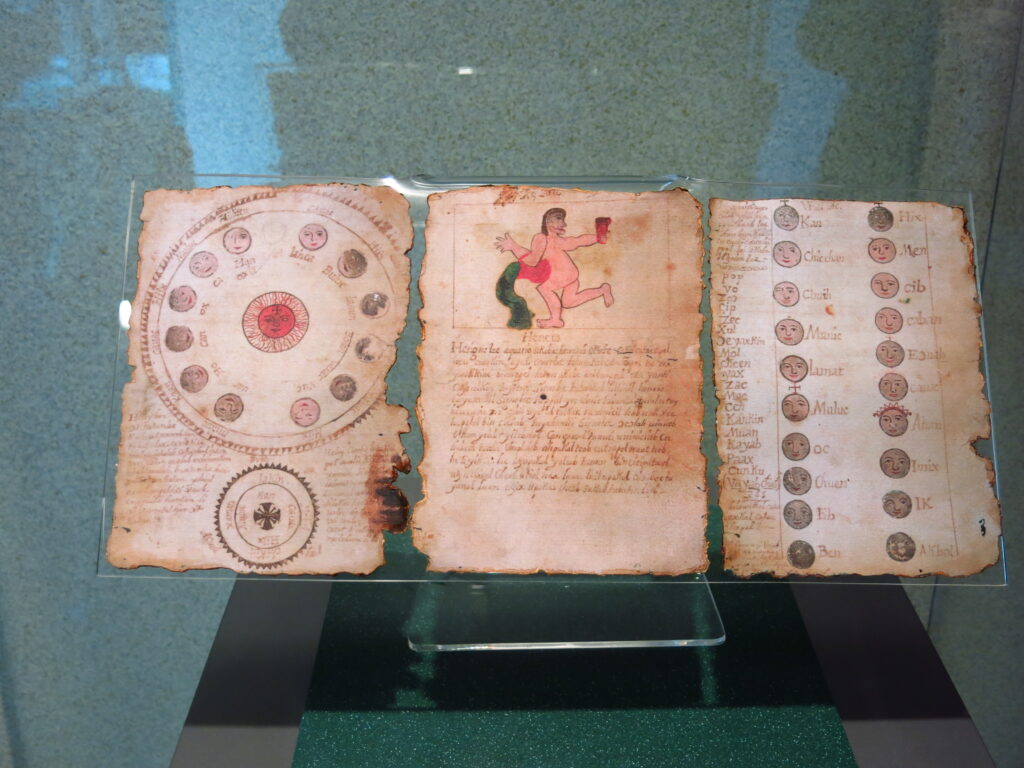

Could there be clues written on paper? Four Maya ancient bark paper books, called codices, survive to this day. In addition, there are the Maya Chronicles, accounts of Maya myth, with presumably a sprinkling of truth, written by Maya scribes after the Spanish conquest. The scribes wrote based on memories handed down generation to generation. There are various chronicles, each named “Chilam-Balam”, and each accounts for the activities in their various regions. The Chilam-Balam of Chumayel, written by a Christian-converted Maya—Don Juan Hoil—in 1782, is perhaps the chronicle most pertinent to the Chichen Itza area. And Spanish conquistadores, most notably Bishop Diego de Landa, recorded the legends related by the living Maya of his time. Despite the fair amount of surviving Maya texts, historians have not been able to find a clear reference in the codices or chronicles to support a Toltec conquest or occupation of the Maya. Likewise, the chacmool is not mentioned or depicted in any of the Maya books or codices. And, while the Aztec occupied central Mexico after the Toltec, the same is true of the Aztec chronicles; no mention of a Toltec conquest of the Maya or the chacmool.

The Chilam-Balam of Chumayel does, however, include a passage that indicates the Itza-Maya, not the Toltec, may have retaken Chichen Itza around the time in question. The passage states, “Katun 4 Ajaw is the eleventh katun according to the count. The katun is established at Chichen Itzá. The settlement of the Itzá shall take place

Still, there are problems with the Chilam-Balam of Chumayel. First, is the book a statement of fact or fantasy? Even if it represents original fact, a lot can be garbled generation to generation. Also, the Maya Chronicles are not easy to decipher and much can be lost in translation. They were written in Maya using European script, translated to Spanish and then English. As for the date cited, the Maya Chronicles use the short count calendar system of 256-year cycles. That means K’atun 4 Ajaw comes around every 256 years. So, in which cycle did the Itza arrive? K’atun 4 Ajaw could correlate to 20-year periods ending in AD 731, 987, or 1243. While much of this data is subject to interpretation, the Itza-Maya do seem to have been major players. Could the Itza-Maya have been the link between Tula and Chichen Itza?

Chichen Itza is thought by some to have been a center of trade for the Itza-Maya, who maintained trade routes along the Gulf coast and inland during the classic and post classic period. Quirigua in Guatemala and Las Mercedes in Costa Rica, both home to at least one chacmool, are located near the Gulf coast. Quirigua in particular, located in the Motugua valley, is known to have pretty much controlled the trade in jade, the vast majority of which originated in the surrounding area along the Motugua River. Jade artifacts have been found throughout Mesoamerica. And there is evidence that this site, having been constructed early in the classic period, was abandoned, and then reoccupied in the AD 900 – 1200 period, the same period encompassing the new construction in Chichen Itza.

North, beyond the Yucatan in the Veracruz/Tabasco area, not too far from Tula, Cempoala is also home to a chacmool figure. This area is close to the Gulf coast and within range of the Itza-Maya trade routes. In fact, while there is a belief that the Itza-Maya originated in the Peten area of Guatemala, there are also indications they settled, or perhaps even originated, in the Tabasco area. This was the homeland of the Chontal-Maya, thought to at least be related to the Itza-Maya. The Chontal-Maya considered themselves ancestors of the Olmec, a much earlier Preclassic civilization many believe to be the mother culture of Mesoamerica. It was in this area that in 1519 Hernán Cortés recruited a woman, renamed ‘Marina’ after her baptism, who spoke Maya and Nahuatl. She served as interpreter during the conquistador’s march into central Mexico, and his conquest of the Aztec. This would certainly indicate that the Chontal-Maya, and perhaps the Itza-Maya, were familiar with the Nahuatl language. Also, the Chilam-Balam of Chumayel does refer to the Itza as foreigners who spoke the Maya language brokenly. And, a significant Ch’olan (Chontal-Maya) linguistic component has been detected in the Chichen Itza inscriptions, lending further support to the connection between the Itza, the Chontal Maya, and Chichen Itza.

Perhaps it was the Itza-Maya who were responsible for the “Toltec” architectural and artistic elements at Chichen Itza and Tula, after having been influenced through centuries-long contact with people along their trade routes. Perhaps common elements reach all the way back to the Olmec. The truth may never be known. Just trying to understand what we do know can be frustrating. As with most things Mesoamerican, timing is highly subjective, opinions vary, and seldom do the elements line up into a clear picture. Even if it were known who did what to whom and when, it probably would not explain the function of the chacmool or the large concentration of chacmool statuary at Tula and Chichen Itza. The mystery of the chacmool will likely remain a mystery.