Mesoamerica’s Ancient Visitors

By Victor Zugg

It may be that all three major human races inhabited, or at least visited, Mesoamerica very early in its history. Typically the early inhabitants of Mesoamerica—the Olmec of Mexico’s Gulf coast, the Maya of southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, and the Toltec/Aztec of Central Mexico—are ‘Indian’ in appearance. These people predominately had, and still have, darker skin, black hair, a long hooked nose, and no facial hair. Even today, there are plenty of ethnic Olmec, Maya, and Aztec living in their respective regions.

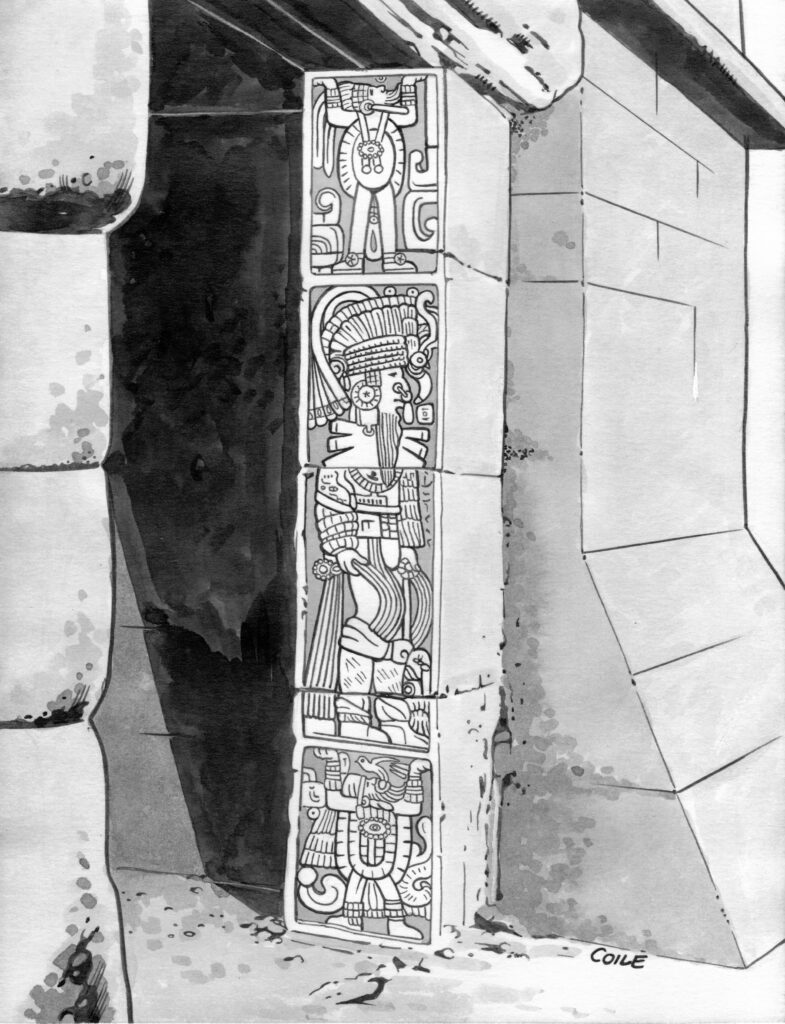

‘Native’ Mesoamerican. Bas relief carving currently on display in the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City.

The Olmec are thought to have been the mother culture of Mesoamerica, giving rise to many aspects of the later Maya and Aztec cultures. Situated in the current Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco, on the Caribbean coast just north of the Yucatan, these people likely reigned from around 1600 – 400 BC. No one knows from where they came, when they arrived, or even their actual name. The term Olmec, meaning rubber people, was given to them by the much later Aztec of central Mexico, because of the rubber trees in the Olmec area. The Olmec are thought to be the first to develop rubber, used for rubber balls in the games played in the ‘ball courts’ found in the Olmec region and throughout Mesoamerica.

The Maya reigned supreme well after the Olmec, in the range of AD 200 – 1100 or so. The Maya are renowned for their massive stone pyramids, writing, calendar, understanding of the stars, ball games and courts, and sacrifices.

The Aztec dominated their region in central Mexico until conquered by the conquistadores of Hernán Cortés in 1521. Like the Maya, the Aztec people are noted for their magnificent structures, writing, calendar, stars, ball games and courts, and sacrifices.

However, in addition to these ‘natives’, the archaeological record indicates there were others who did not fit the native profile. These ‘others’ in appearance are closer to the mainstream three major races—Caucasoid (European), Negroid (African), and Mongoloid (Asiatic)—than they are to the natives. Take a look at some renditions that might support very early habitation or visitation by the ‘others’.

The Bearded Man

Reportedly, a bearded Caucasian man was revered throughout early Mesoamerica and even by the Inca empire, much further south in Peru. This bearded man, presented in rock bas relief and artifacts throughout Mesoamerica, has come to be associated with a particular creator god known by different names: Viracocha for the Inca, Kukulkan for the Maya, and Quetzalcoatl for the Aztec. All three names mean feathered serpent in their respective languages. The god, represented by the feathered serpent, is present throughout Mesoamerica in art, artifacts, and ancient manuscripts. The feathered serpent is then further represented by the bearded man through a confusing mix of ancient myth and 16th century Spanish chronicles. The tales depict Kukulcan, Quetzalcoatl, and Viracocha as an actual bearded god-like man who walked among the people teaching basic civilization, including agriculture, medicine, and writing.

Probably the earliest rendition, and one of the best depictions of the bearded man, is from the heartland of the Olmec—Monument 13, “The Ambassador”— from La Venta, in the state of Tabasco. It doesn’t take much imagination to see this character as Caucasian and distinctly ‘Phoenician’ in appearance, given the beard, turban, and pointed footwear.

Another equally interesting portrayal from the Olmec region is the Alvarado Stele depicting a bearded man with arguably non-Olmec facial characteristics, but wearing more of what could be considered ‘Indian’ garb: loin cloth, plumed headdress, no footwear. Could this be a very early example of “going native?”

If so, the relief carved in the pillar of the temple atop the El Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza, deep in Maya territory, might depict a further iteration of going native. This individual sports a long beard while dressed in full Maya regalia. El Castillo was and is also referred to as the Temple of Kukulcan.

Throughout Mesoamerica there are many other examples, carved in stone and created in art, of a bearded man. He was obviously held in high regard. Was he a god, an ancient wise visitor from Europe, or did he actually exist at all?

A Gulf Coast bearded figure sculpted in mud. Thought to be from the classic period (AD 1 – 900). On display in the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City.

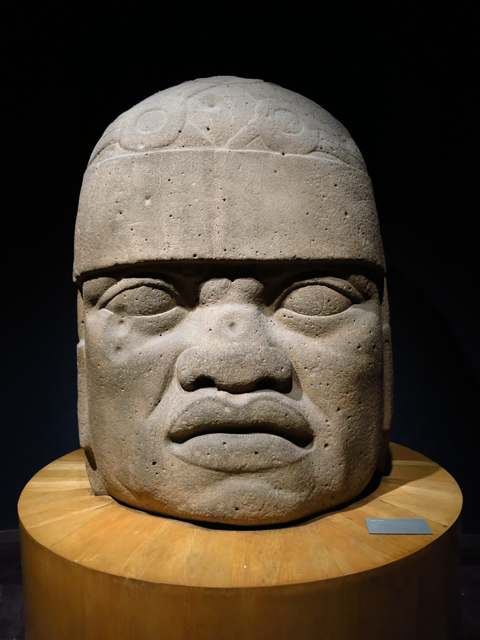

Colossal Heads Among the Olmec

The colossal heads of the Olmec portray distinct Negroid features, including high cheek bones, fleshy cheeks, and flat noses. These characteristics can still be found today among the inhabitants of the Olmec region.

Starting with the first discovery in the 19th century, a total of 17 colossal stone heads have been found, several after being completely buried. There are 13 heads from present-day Veracruz, and 4 from Tabasco. The heads themselves cannot be dated but, given the context of the finds, most were likely in place by 900 BC. All were carved from solid basalt boulders obtained from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas Mountains, up to 100 miles from the heads’ place of discovery. The heads range in height from 11 feet to just under 5 feet, and in weight from approximately 40 tons to 6 tons. What appears to be a helmet, each unique, adorns each head. The helmets have led some historians to speculate that the heads depict kings, warriors, or some kind of sports figures. All the heads were carved with flat backs, presumably to make them easier for transport.

Transporting the basalt boulders would have been a major undertaking, since it would have meant passing over hilly land, through swamps, and over bodies of water all without the wheel or beasts of burden. And carving the heads would have been no easy task either, since the Olmec had no metal tools. Carving would have meant pounding rock against rock, a very slow process. Carving and transporting them obviously required considerable time and effort, so they must have meant a lot to whoever ordered their construction and placement. And then to bury them after all that effort presents an even bigger mystery.

Were these heads meant to depict ancient visitors from Africa? There is a definite resemblance, but is that proof enough?

Mesoamerica’s Asian Influence

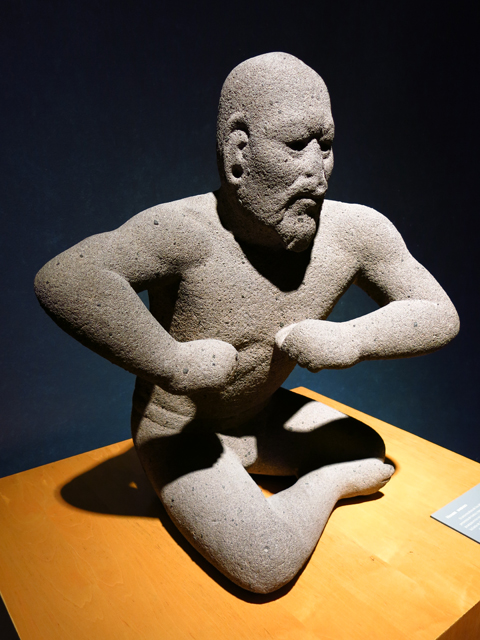

Another intriguing work of art from the Olmec region is what has been termed “The Wrestler”, also known as Antonio Plaza Monument 1. It was unearthed by a farmer in 1933, in Veracruz, near Minatitlán and the Uxpanapa and Coatzacoalcos rivers. The statue stands 26 inches tall. The mustache and goatee, in conjunction with the facial characteristics, give this statue a distinctive Asian appearance. Even without the mustache and goatee, this sculpture is unique with regard to style and form among all other Olmec pieces.

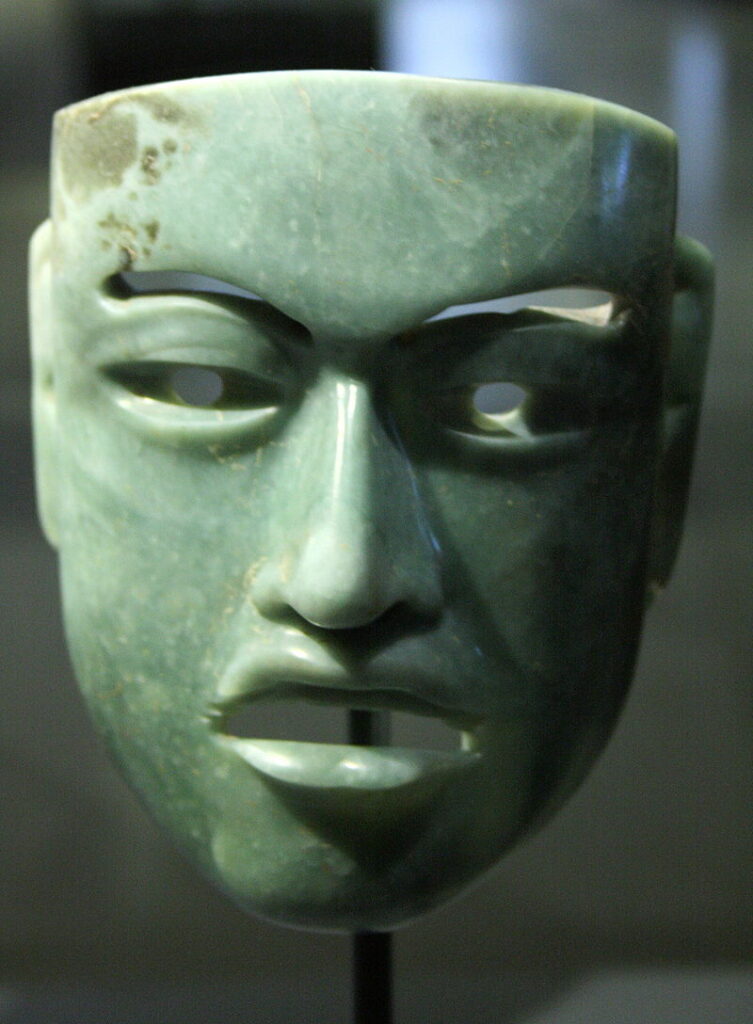

This Asian flair continues in many of the masks carved in semi-precious mineral stone, especially jade, from the time of the Olmec. All Mesoamericans, from all eras, valued jade and used it in art, adornments, and for tools. Olmec pieces, especially, are often particularly complex and refined. The source of Mesoamerican jade was lost for centuries until the 1950s, when an intense search revealed jade mines in the Motagua Valley of Guatemala. Guatemala would have been a trek, on foot or by boat, for the Olmec but. nonetheless, based on the results of in-depth research reported by mineralogist George Harlow in his article, Hard Rock, it all came from Motagua.

Asian similarities; maybe. But were early Mesoamericans visited by ancient Chinese from over the Pacific, who influenced facial features, development, and art? Did they leave their image carved in jade?

Inhabitants or Visitors?

With regard to a Mesoamerican Caucasian bearded man there is potentially one giant fly in the ointment. Rock cannot be dated. Bas reliefs and sculptures of the bearded man could have been carved in 900 BC, AD 900, or AD 1522. Many historians have pointed out that the idea of a bearded white god first gained expression in the 16th century Spanish conquistador accounts of being greeted as ‘white gods’. Pedro Cieza de León, a conquistador, first chronicled the idea after Francisco Pizarro’s encounter with the Inca. The idea has grown and spread ever since. Interpretations vary on what appear to be ‘beards’ on other artifacts prior to the Spanish. And with regard to Monument 13, The Ambassador, while the Phoenicians from the Mediterranean were extremely adept at ocean trade and travel, there is no real evidence to support they ever visited Mesoamerica.

And do the colossal heads depict ancient Negroid visitors, or just existing Mesoamericans with slightly different facial features? Perhaps inhabitant Mesoamericans with these particular features just happen to make good warriors or sports figures and were revered as such. There is nothing written, drawn, or in art that gives these heads context, beyond the dirt in which they were found, so there is presently no way to know who they represent.

And finally, does Mesoamerican art support a visit by people from ancient China, thus influencing art and characteristics? If they did they did not bring any of their Chinese jade. None of the Mesoamerican jade pieces found so far are consistent with the mineralogy of jade from the Orient. As for The Wrestler and its ‘Asian’ characteristics: Dr. Karen Olsen Bruhns, Professor Emerita Department of Anthropology, San Francisco State University, and Dr. Nancy L. Kelker, Professor of Art History at Middle Tennessee State University, in their book Faking Ancient Mesoamerica (2009), consider The Wrestler statue likely a poorly conceived fake. They point to its atypical proportions and anatomical detail as being more consistent with western art. Also, the stone may not be correct for the area. Professors Bruhns and Kelker summarized their findings in a March 13, 2011 article in the online magazine Mexicolore.

“Since its purchase by the museum (National Anthropology Museum, Mexico City) in 1964, a lot of ink has been spilt by scholars attempting to rationalize the eccentricities of this beautifully carved piece. But no amount of hyperbole can excuse the very real fact that the work is consistent with a western canon of art rather than with an Olmec one. The piece exhibits several eccentric characteristics pointing to its maker’s familiarity with western art, including a Renaissance ratio of proportion, Classical anatomical detail, and contrappostal movement. There are also several characteristics that illustrate the artist’s unfamiliarity with Olmec monumental art, such as an incorrect loincloth, bare head, ear lobes drilled rather than carved with ear spools, and use of the wrong type of stone.”

Other equally noted archaeologists and historians disagree and suggest that its uniqueness and dissimilarity with any other artifact contributes to its likely authenticity.

Do these ‘others’ represent ancient inhabitants with varying characteristics, or do they depict ancient visitors from faraway lands who left their mark on early civilizations? There are no definitive answers for the bearded man, the colossal heads, or what might be an Asian influence. There is not enough information to draw firm conclusions. And with so little information available about many aspects of Mesoamerica, the field remains ripe for speculation. Maybe one day someone will find the Rosetta Stone of Mesoamerican ethnicity but, until then, it will all likely remain a mystery.